In the Field: Testing the Timbers

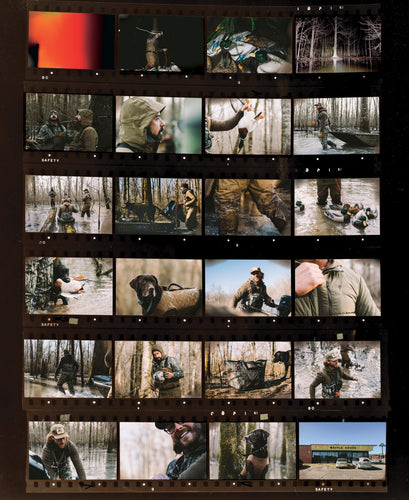

Words by Aaron Zachary | Photos by Isaac Neale

It’s 6am and 12 degrees. You’re watching ice form at an alarming rate – around trees, around your pant legs. In fact, you tripped about 20 minutes ago and just realized your jacket cuff is frozen to the soggy handwarmer in your pocket.

Somewhere, a few trees over, there are two guys from Georgia both named Jacob. Earlier they were just mere strangers on a boat – at this point they’re practically family. You see the faint glow of a freshly-lit cigarillo, followed by the smell of a gas station pickle, followed by another cigarillo. From either excitement or cold you hear a lab losing its mind nearby. Someone starts splashing water with their boots to imitate the safe sounds of ducks landing, and you join in just for the chance to feel your feet again.

But now all of that work is starting to make sense. Backpacks are strapped to the trunks of ancient hardwoods, a buffet of mallard and pintail decoys are lovingly placed, and a chaotic symphony of calls are rising from every hunting hole across the flooded forest.

From the deep darkness, rhythmic wing beats merge into the beats of your heart. You realize you haven’t thought about anything, or anyone, outside of this experience, since the alarm chimed at 1 am. For the last few hours you didn’t have to worry about anything other than making it out, but now that you’re here, the reward is 25,000 acres of public land waiting for first light.

This in-between moment is disrupted by the faint break of sunlight, shattered by hundreds of winter-naked trees. Despite all the work and discomfort, despite the shelf of ice protruding from your boots at the water line, you reach the same conclusion:

It’s just good to be out here.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.