The Retrieve

Words by Ryan Brod / Illustrations by Joelle Cubero

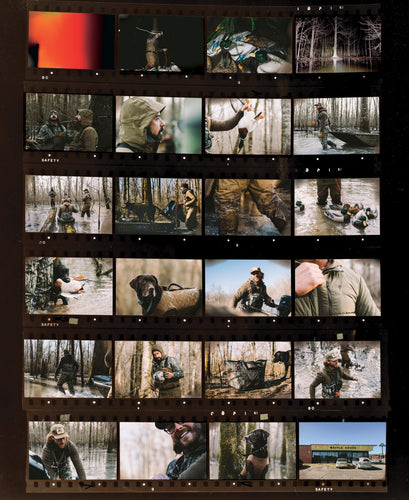

The flock arrived late, just a few minutes left of shooting light. Not the mallards or wood ducks I expected but instead five or six Canada Geese, honking and gliding in formation over the treetops. The V flared at my decoys, hovered as if considering a water landing on this small marshy pond. I stood, picked a target, and fired. Missed. One of the geese, the trailer, veered from the group. I fired again, missed, pumped the shotgun and fired once more. The slightest flinch, then the goose bailed into the trees like a doomed airliner. I feared I’d crippled but not killed it.

Mazie leapt from the blind into the pond. We never trained her quite right and she—a lean, graceful swimmer, a yellow lab with a magical nose—always assumed we’d killed something. When we missed, which was more often than I liked to admit, she’d swim in circles, searching for the duck she was sure we’d downed, looking back at me as if to ask: is this some kind of cruel trick? That evening, I called her off eventually and we searched the pond’s forested edge until it was too dark to see.

There’s a nauseated feeling that accompanies crippling an animal, akin to mild seasickness. I didn’t sleep well that night, replaying my errant shot and chiding myself for taking it at all.

In the morning I rose before sunrise and returned to the pond with Maizie, who seemed to have slept just fine, likely dreaming of wingbeats and the sweet smell of wood duck feathers. I idled us to where I’d fired the evening before, pulled the skiff on shore, and called Maizie over. “Find the goose,” I said, “go get it, go ahead!” Maizie bounded off into the woods.

I stood there waiting. The air carried the damp, earthy smells of autumn. I knew Maizie was out there utilizing her superior nose, following scent currents that I would never register. Five minutes passed. I thought of calling her but waited. Ten minutes. Fifteen. I feared Maizie had gotten lost but knew better, and continued waiting.

We fancy ourselves predators though most of us are average at best. We’re aided by optics and motion sensor cameras and camouflaged clothing and projectiles that move faster than we can comprehend. We need all the help we can get. Meanwhile, the prey we seek have honed their senses over hundreds of thousands of years. How absurd it is to think ourselves superior, I thought, to not recognize the gifts we receive when we’re lucky enough to harvest game. How lucky we are to have our hunting dogs along with us.

Fifteen minutes, twenty. Finally I called Maizie. I worried she’d hurt herself or gotten turned around in the thick, tangled woods, or that maybe she’d made it out to the gravel road and—worst case scenario—had been struck by a passing vehicle. It was unlikely, given the lack of traffic—so I tried to push the thought out of my mind, and then she came leaping over a fallen birch, the goose in her mouth still very much alive.

“Good girl!” I shouted, and Maizie delivered the goose, her tail wagging in tight circles.

I killed the goose with my hands. One of its wings was broken, but otherwise it looked fine, would have lived a while in the woods until something—some predator more skilled than myself—found and dispatched it.

Maizie kept nuzzling the still-warm goose. I patted her head and scratched her ears, which she always loved, and then she bounded in circles around me, around the goose, barking and nipping at its limp wings, proud of herself, it seemed. I idled the boat back to the truck, loaded up and headed home, the goose resting delicately in the bottom of the boat. On the ride I thought about recipes, about whether or not I would give some meat to the dog. She had certainly earned it.

Fifteen years’ later and Maizie is long gone, buried at the edge of the woods where deer come every spring to eat fresh shoots of grass. She had a nose on her. I still tell friends about the live goose she chased and retrieved, about the wonders of her senses. I tell them how happy she was to present me with an animal, each one a small and meaningful gift. I think of Maizie when the days get shorter. I think of her when the leaves let go of the trees, tumbling and gliding finally to the waiting earth.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.